When you get a safety communication about a medication, medical device, or vaccine, it’s not just a notice-it’s a signal to pay closer attention to your body. These alerts come from the FDA, CDC, or your healthcare provider when something potentially harmful is discovered. Maybe a batch of pills has unexpected side effects. Maybe a blood pressure monitor gives false readings. Or maybe a new vaccine shows rare heart inflammation in a small group. Whatever the case, symptom monitoring is your next step. It’s not optional. It’s how you protect yourself and others.

Understand What the Safety Communication Means

Not all safety alerts are the same. The FDA issues them for drugs, devices, and biologics. The CDC uses them for infectious disease outbreaks or vaccine concerns. The message might say "monitor for fever and chest pain" or "watch for unusual bruising." If it doesn’t specify symptoms, call your doctor. Don’t guess. The alert should clearly list what to look for. For example, after the 2021 J&J vaccine safety notice, people were told to watch for severe headaches, abdominal pain, or leg swelling within three weeks. Those weren’t random suggestions-they were based on actual case data.Know Your Risk Level

Your monitoring plan depends on how exposed you were. High-risk means direct contact with a faulty product-like taking a recalled medication daily. Medium-risk might mean you took one dose before the alert. Low-risk could mean you own the device but haven’t used it. The CDC breaks this down simply: high and medium risk need active monitoring. That means someone checks in with you daily-by phone, text, or app. Low-risk? You self-monitor. You check yourself, and only report if something changes. Most people fall into low-risk. But if you’re immunocompromised, pregnant, or over 65, treat it as medium-risk. Better safe than sorry.Track the Right Symptoms

Write down exactly what the alert says to watch for. Don’t rely on memory. Use a notebook, a notes app, or a printable checklist. If the alert mentions "fatigue," be specific. Is it mild tiredness after lunch? Or are you sleeping 12 hours and still exhausted? If it says "rash," note where it shows up, how it feels (itchy? burning?), and if it spreads. The FDA’s 2023 guidelines now require standardized symptom scales-rate each symptom from 0 to 10. Zero means nothing. Ten means unbearable. This helps doctors spot patterns. A 2022 study in Health Affairs found that using a 0-10 scale reduced miscommunication by 53% compared to vague descriptions like "I felt weird."Set a Monitoring Schedule

Frequency matters. For high-risk exposures, check yourself twice a day-morning and night. For low-risk, once a day is enough. Set alarms. Use your phone. Mark it on a calendar. Don’t skip days because you feel fine. Symptoms can appear days after exposure. The CDC’s v-safe system, used for COVID-19 vaccines, sends daily text reminders. People who used it reported symptoms 3 days earlier than those who didn’t. If you’re using an app, make sure it’s HIPAA-compliant. Most free apps aren’t. Look for ones linked to your hospital or the CDC. Symptomate, for example, uses CDC-approved symptom lists-but 82% of 1-star reviews mention privacy fears. If you’re unsure, paper is safer than an untrusted app.Know When to Call for Help

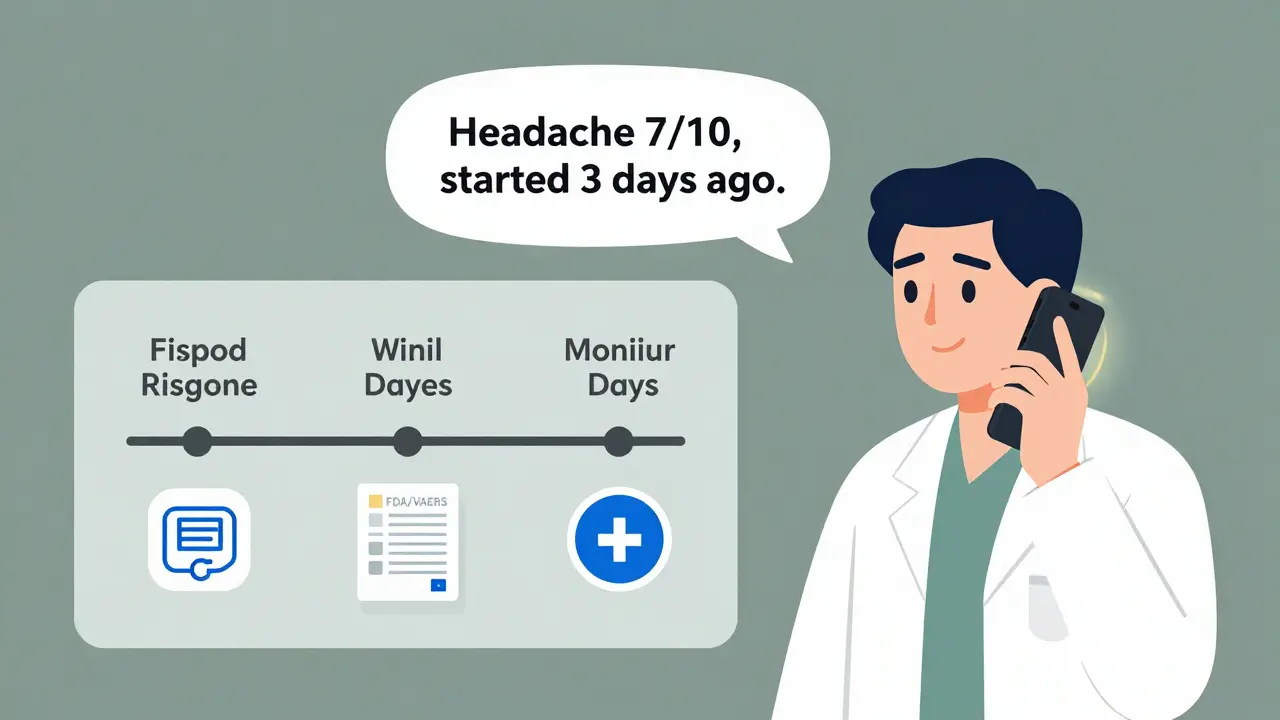

Not every symptom needs an ER visit. But some do. The alert should tell you what counts as an emergency. For example: chest pain that lasts more than 5 minutes, sudden weakness on one side of the body, trouble breathing, or a fever over 102°F that doesn’t break with medication. If you’re unsure, call your doctor or a nurse line. Don’t wait. A 2020 study in JAMA Internal Medicine showed that patients who reported symptoms within 24 hours had a 31% lower chance of hospitalization. The SBAR method (Situation, Background, Assessment, Recommendation) works wonders here. Say: "I took the recalled drug on January 2. Yesterday I got a headache and dizziness (Situation). I’ve been monitoring since the alert (Background). My headache is a 7/10 and won’t go away (Assessment). Can I come in today or should I go to urgent care? (Recommendation)." Clear communication saves time-and lives.Document Everything

Keep a log. Date, time, symptom, severity, what you did (took Tylenol? rested?), and how you felt afterward. This isn’t busywork. It’s evidence. If you end up in the hospital, your log helps doctors connect the dots. OSHA requires employers to keep exposure records for 30 years. The FDA requires manufacturers to keep symptom data for 2 years. Your personal log? Keep it forever. You might need it for insurance, legal claims, or future health decisions. If you use an app, export your data weekly. Screenshots aren’t enough. PDF or CSV files are.Avoid Common Mistakes

People mess up in predictable ways. Here’s what not to do:- Don’t ignore mild symptoms because "it’s probably nothing." Rare side effects start small.

- Don’t assume the alert applies to everyone. If you didn’t take the drug, you don’t need to monitor.

- Don’t wait for a doctor to call you. Most won’t. You have to act.

- Don’t use unverified apps. Many collect your data and sell it.

- Don’t stop monitoring after a week. Some reactions take 30 days to show up.

Use Tools That Work

You don’t need fancy tech. But if you want help, choose wisely. The CDC’s v-safe system is free, secure, and integrates with state health databases. Epic and Cerner systems are used in 72% of U.S. hospitals-if you’re a patient there, ask if they have a built-in symptom tracker. For non-hospital users, the FDA’s MedWatch portal lets you report symptoms directly. You can also use a simple Google Form or Excel sheet. The key isn’t the tool-it’s consistency. A 2023 AHRQ report found that clinics embedding monitoring into daily routines (like morning vitals checks) saw 61% less abandonment than those treating it as a separate task.What Happens After You Report?

Once you report a symptom, your data goes to the FDA’s Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) or the CDC’s VAERS. These systems look for patterns. If 50 people report the same issue, the agency investigates. That’s how dangerous drugs get pulled. Your report matters-even if you think it’s minor. In 2022, a single report of blurred vision after a diabetes device led to a nationwide recall. You’re not just protecting yourself. You’re helping protect thousands.What If You Missed the Alert?

It happens. You were on vacation. You didn’t check email. You’re not behind. If you suspect you were exposed, start monitoring now. Symptoms don’t have expiration dates. If you took a recalled drug 6 weeks ago and now have unexplained fatigue, get checked. The CDC says monitoring is still valuable up to 90 days after exposure for certain products. Don’t assume it’s too late. Your body doesn’t follow deadlines.Stay Calm, Stay Alert

Safety communications can scare people. But they’re designed to help, not panic. Most alerts lead to no serious outcomes. But if you’re not monitoring, you’re flying blind. The goal isn’t to live in fear-it’s to be informed. Track what you’re told to track. Report what’s unusual. Use simple tools. Stay in touch with your doctor. You’ve got this.What should I do if I don’t understand the safety communication?

Call your doctor or pharmacist. Don’t rely on internet searches. Safety communications are written for professionals, not patients. Ask them to explain what symptoms to watch for, how long to monitor, and whether you need to stop using the product. If you’re on Medicare, you can call 1-800-MEDICARE for free help.

Can I stop monitoring if I feel fine after a week?

No-not unless the alert says so. Some side effects take weeks to appear. For example, a recalled blood thinner might cause internal bleeding only after prolonged use. The FDA recommends monitoring for at least 30 days after exposure for most drugs and devices. If the alert doesn’t specify, assume 30 days is the minimum.

Are symptom tracking apps safe to use?

Only if they’re HIPAA-compliant and linked to a trusted health system. Most free apps aren’t. Check if the app is offered by your hospital, the CDC, or the FDA. Avoid apps that ask for your Social Security number, credit card, or location data. The HHS Office for Civil Rights found 67% of symptom apps in 2021 didn’t meet privacy standards. Paper logs are safer than untrusted apps.

What if I report a symptom and nothing happens?

That’s okay. Reporting doesn’t mean immediate action-it means data collection. The FDA and CDC need hundreds or thousands of reports to spot a pattern. Your report adds to the evidence. In 2022, over 12,000 reports helped trigger a recall of a faulty insulin pump. You may never hear back, but your report could save someone else’s life.

Do I need to tell my employer about my symptoms?

Only if your exposure happened at work-like using a faulty medical device on the job. In that case, OSHA requires you to report workplace-related health issues. For personal medication use, no. Your medical info is private. But if you’re a healthcare worker and were exposed to a recalled drug or device, your employer may require active monitoring. Follow your workplace’s policy.

Ted Conerly

January 9, 2026 AT 00:42Just followed this guide after getting a recall notice for my blood pressure monitor. Started tracking my symptoms with a simple Google Sheet-time, reading, how I felt. No app needed. Two days in, noticed my headaches were hitting a 7/10 every afternoon. Called my doc. Turned out it was the device giving false lows, and my body was overcompensating. This post saved me from a potential stroke. Do the work. It’s not scary-it’s smart.

Faith Edwards

January 9, 2026 AT 11:11One is left to wonder whether the average American possesses the cognitive capacity to comprehend even the most rudimentary public health directives. The notion that one must *write down* symptoms-like a child learning cursive-is not merely quaint, it is a tragic indictment of our collective intellectual erosion. The FDA, in its infinite wisdom, has been reduced to babysitting adults who cannot differentiate between ‘mild fatigue’ and ‘I just watched six hours of TikTok.’

Jay Amparo

January 10, 2026 AT 13:34Hey everyone, I’m from India and we don’t have easy access to apps or even reliable internet sometimes. But I made a paper log-just a notebook, pen, and my phone’s alarm. I track my BP meds after the recall. Every night at 9 PM, I write: symptom, score, what I did. My aunt, 72, started doing it too. We check in every Sunday. It’s not tech-it’s care. And care doesn’t need Wi-Fi.

Lisa Cozad

January 11, 2026 AT 03:53I used the CDC’s v-safe app after my booster. It sent me daily texts asking how I felt. I didn’t think it would help, but I did it. On day 11, I had a weird tingling in my arm. I clicked ‘report.’ Two days later, my local health dept called to thank me. Turns out, 12 others had the same thing. They’re reviewing the batch. I didn’t do anything dramatic-I just showed up. That’s all it takes.

Saumya Roy Chaudhuri

January 11, 2026 AT 07:01You people are so naive. The FDA doesn’t care about your little logs. They’re a corporate puppet. Every ‘safety alert’ is a PR stunt to delay a full recall while they negotiate with the manufacturer. If you really want to protect yourself, stop taking anything prescribed. Go herbal. Go raw. Go live. Your body knows better than some bureaucrat in a lab coat with a 401(k). And don’t even get me started on ‘HIPAA-compliant apps’-that’s just marketing jargon for ‘we’ll sell your data to Big Pharma anyway.’

Ian Cheung

January 11, 2026 AT 13:57Been tracking my symptoms since the J&J alert last year. Wrote down every headache, every dizzy spell. Didn’t think much of it. Then last month I looked back-my 7/10 headaches always came after lunch, right after I took the med. Turns out it was the grapefruit juice I drank with it. No one told me that. But my log did. Paper beats algorithms every time. Just write it down. Seriously. Do it.

anthony martinez

January 12, 2026 AT 16:53Wow. A 15-page essay on how to not die from a drug you took once. Did we forget we’re adults? Or did we just outsource our brains to a checklist? Next they’ll send us a PDF titled ‘How to Breathe: A Step-by-Step Guide.’

Mario Bros

January 14, 2026 AT 14:09Bro. Just use a notes app. Name it ‘Symptom Tracker.’ Every morning, type: ‘No issues.’ Every night, type: ‘Headache 3/10, took ibuprofen, slept fine.’ That’s it. No app. No stress. No drama. You don’t need to be a scientist. Just be consistent. And if you forget? Set a reminder. Your future self will high-five you.

Christine Milne

January 14, 2026 AT 23:35It is an astonishing abdication of personal responsibility to rely upon governmental advisories in the first instance. In the United Kingdom, we are taught to consult peer-reviewed literature, not algorithmically generated checklists from agencies whose funding is contingent upon public panic. The notion that a layperson can accurately assess symptom severity on a 0–10 scale is not merely misguided-it is a dangerous overreach of pseudoscientific populism. One would do better to consult a physician, or, better yet, abstain entirely from pharmaceutical intervention.