When you take a generic pill for high blood pressure, you expect it to work just like the brand-name version. That’s because generics are made of simple chemicals, and scientists can copy them exactly. But biosimilars aren’t like that. They’re copies of complex biologic drugs - proteins made inside living cells, not labs. And copying them? It’s like trying to rebuild a Ferrari using only photos of the engine, without the blueprints.

Why Biosimilars Aren’t Like Generics

Generics are small molecules. Their structure is fixed. If you mix the right chemicals in the right order, you get the same result every time. Biosimilars? They’re large, folded proteins - sometimes over 100 times bigger than a typical generic drug. They’re made by genetically engineered cells - usually Chinese hamster ovary cells - that act like tiny factories. These cells don’t just produce a molecule. They modify it. They add sugars. They fold it just right. They tweak it in ways we can’t fully control. That’s why the FDA and EMA don’t call them "identical." They call them "highly similar." Even tiny differences in how the cells are grown can change how the drug behaves in your body. One study showed that changing the pH of the culture medium by just 0.2 units altered the glycosylation pattern - the sugar chains attached to the protein - enough to affect how long the drug stayed in your bloodstream.The "Process Defines the Product" Problem

There’s no secret formula you can reverse-engineer. The originator company doesn’t share how they feed their cells, how they stir the bioreactor, or what exact nutrients they use. So biosimilar makers have to figure it out themselves - through trial and error, over years. Think of it like baking a sourdough loaf. You know what the final loaf looks like. But you don’t know the starter’s age, the flour blend, the temperature during proofing, or how long the baker let it rest. You try different combinations. You tweak. You test. You fail. You try again. And every time you change one thing - say, the water temperature - the whole loaf changes. In biosimilar manufacturing, this happens at every step: cell line development, fermentation, purification, formulation, and filling. Each step introduces variability. And regulators demand that the final product matches the original in every measurable way - structure, purity, stability, and function.Glycosylation: The Silent Killer of Consistency

One of the biggest headaches? Glycosylation. That’s the process where sugar molecules attach to the protein. These sugars aren’t just decoration. They control how the drug interacts with your immune system, how long it lasts in your blood, and whether it triggers side effects. The same protein made in two different bioreactors can have completely different glycosylation patterns. Why? Because the cells are alive. They react to oxygen levels, nutrient feed rates, temperature shifts, even the way the tank is stirred. A 5% change in dissolved oxygen can shift glycan profiles by 15%. To match the reference product, manufacturers must map out its entire glycosylation fingerprint - hundreds of sugar variants - then build a process that reproduces it. And they have to do it consistently, batch after batch, for years. One failed batch means millions in losses.

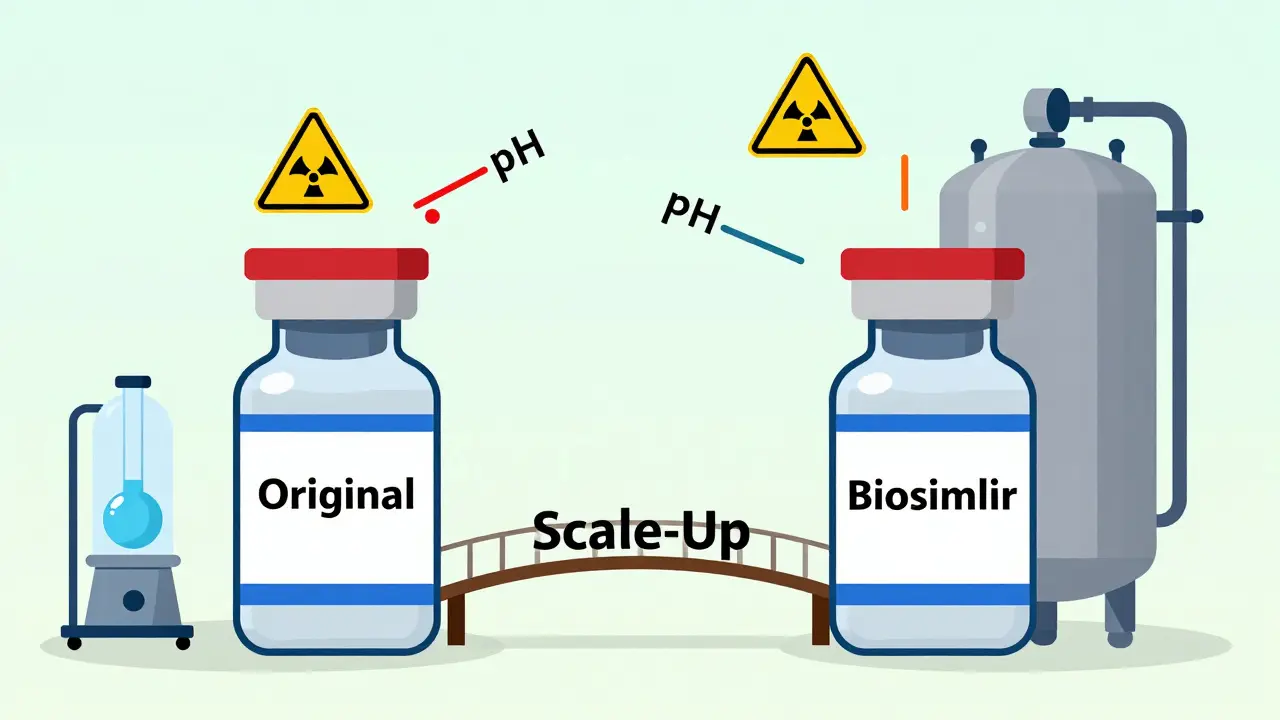

Scaling Up: Bigger Isn’t Better

Getting a biosimilar to work in a 10-liter lab tank is one thing. Getting it to work in a 2,000-liter commercial bioreactor is another. The physics change. Mixing becomes uneven. Oxygen doesn’t distribute the same way. Cells experience different shear forces. Temperature gradients form. The cells get stressed. And when cells are stressed, they make different proteins. Many smaller manufacturers don’t have the space or budget for large-scale bioreactors. Some have to rent time on shared facilities, which means frequent changeovers - and each changeover risks contamination or cross-contamination. Even the type of bag used to store the drug can affect stability. Plastic bags leach chemicals. Glass bottles can adsorb proteins. Every material choice matters.Cold Chain Nightmares

Biosimilars are fragile. Most need to be kept between 2°C and 8°C from the moment they’re made until they’re injected into a patient. Break that chain once - a truck breaks down, a fridge fails, a warehouse door is left open - and the entire batch can degrade. You won’t see it under a microscope. But your body will. A single vial of a degraded biosimilar might trigger an immune response. Or it might just not work. Either way, it’s a patient safety risk and a financial disaster. One manufacturer lost $42 million in a single recall after a refrigerated container failed during transport from Europe to the U.S.Regulatory Maze

Getting approval isn’t just about science. It’s about paperwork. Regulators want data from over 100 analytical tests: mass spectrometry, capillary electrophoresis, NMR, bioassays, binding studies, stability tests. Each test must be validated. Each batch must be documented. Every change - even a new supplier for a buffer solution - requires re-submission. The FDA’s 2023 guidance clarified that manufacturers must prove similarity not just at launch, but throughout the product’s life. That means ongoing monitoring. That means re-validating processes every time you upgrade equipment or move to a new facility. In Europe, the EMA requires clinical trials in at least one indication. In the U.S., sometimes you can skip them if analytical data is strong enough. In India or Brazil? Different rules again. It’s a patchwork. And compliance costs can hit $200 million per biosimilar.

How Manufacturers Are Fighting Back

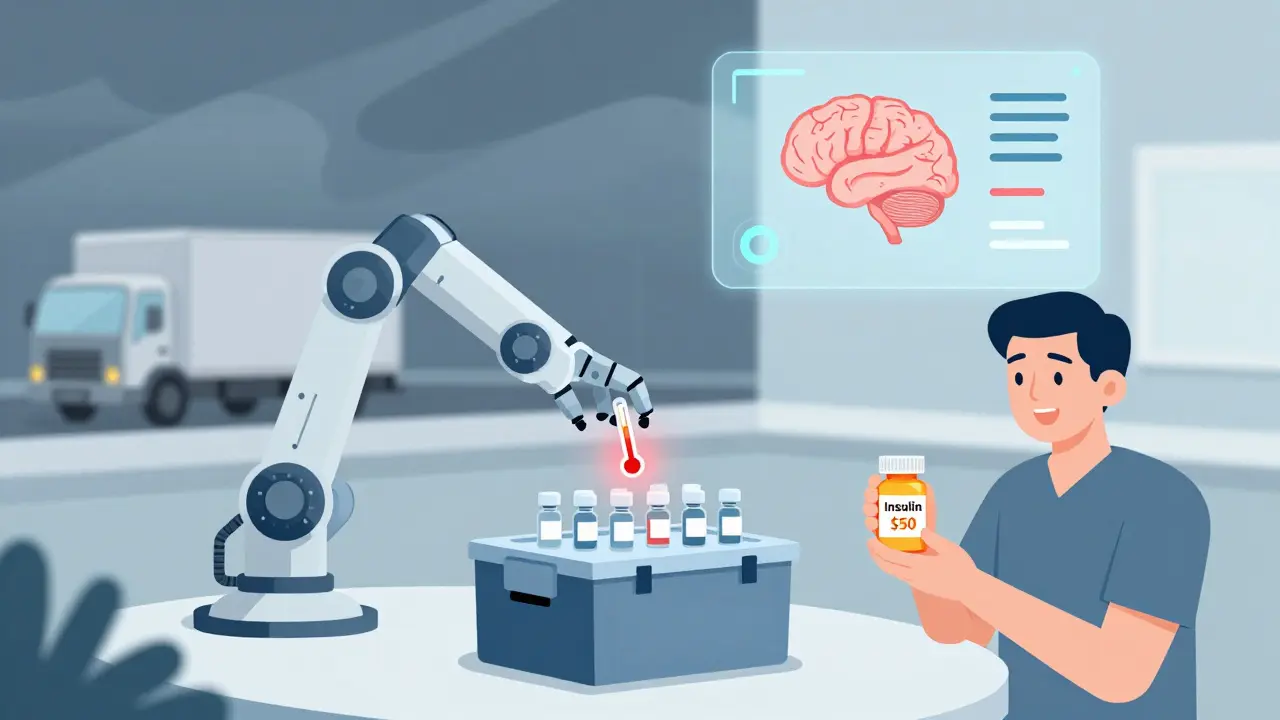

The smartest companies aren’t just trying to copy. They’re innovating. Single-use bioreactors are now standard. No more cleaning stainless steel tanks. No more cross-contamination risks. Faster changeovers. Lower capital costs. These systems let smaller firms enter the market. Process Analytical Technology (PAT) lets them monitor quality in real time. Sensors track pH, dissolved oxygen, cell density, and even glycosylation patterns as the batch runs. If something drifts, the system adjusts automatically - before the product is ruined. Automation is cutting human error. Robotic arms handle vial filling. AI predicts which cell lines will produce the most consistent proteins. Machine learning models analyze decades of batch data to find hidden patterns - like how a 3% increase in glucose feed correlates with a 7% drop in a key glycan. Continuous manufacturing is the next frontier. Instead of making one batch at a time, some companies are moving toward a steady flow - like a factory line for drugs. It reduces variability. It cuts production time from months to weeks. But it’s hard to get regulatory approval for something this new.Who Can Actually Do This?

Only a handful of companies have the money, expertise, and infrastructure to make biosimilars reliably. Big players like Amgen, Samsung Bioepis, and Sandoz dominate. Smaller firms? Many burn out after three failed attempts. The global biosimilar market is expected to hit $58 billion by 2030. But only 15% of potential biosimilars have been launched so far. Why? Because the barriers are too high. The science is too hard. The costs are too steep. And it’s getting harder. Newer biosimilars - like bispecific antibodies or antibody-drug conjugates - have even more complex structures. One drug might require three purification steps, two refolding processes, and five different analytical methods just to prove it’s similar.The Bottom Line

Biosimilars promise cheaper drugs. But they’re not easy to make. Every step - from cell culture to shipping - is a minefield. The margin for error is microscopic. The cost of failure is massive. For patients, the payoff is real: insulin that costs $50 instead of $500. Cancer drugs that are half the price. But behind every vial is a decade of science, millions in investment, and a team of experts fighting to keep a living system stable enough to save lives. This isn’t just manufacturing. It’s precision biology at scale. And it’s one of the toughest challenges in modern medicine.Why can’t biosimilars be exactly the same as the original biologic?

Biosimilars can’t be identical because they’re made by living cells, not chemical reactions. These cells naturally vary in how they produce and modify proteins - adding sugars, folding structures, or adjusting shapes. Even with identical DNA, slight differences in temperature, nutrients, or oxygen can change the final product. Unlike generics, which are exact chemical copies, biosimilars are "highly similar" but not identical - and regulators accept that.

What’s the biggest technical hurdle in making biosimilars?

Glycosylation - the attachment of sugar molecules to the protein - is the biggest hurdle. These sugar chains affect how the drug works in the body, how long it lasts, and whether it causes immune reactions. Reproducing the exact glycosylation pattern of the original drug is extremely difficult because it depends on dozens of variables in the cell culture process, most of which are unknown to the biosimilar maker.

Why is scaling up biosimilar production so hard?

When you go from a small lab bioreactor to a large commercial one, the physics change. Mixing, oxygen flow, and temperature become uneven. Cells experience different stress levels, which alters protein production. A process that works perfectly in a 50-liter tank might fail in a 2,000-liter one. Many manufacturers lack the equipment or expertise to make this transition without losing product quality.

Do biosimilars need clinical trials to get approved?

Sometimes. In the U.S., if analytical and non-clinical data are strong enough, regulators may waive clinical trials. In Europe, at least one clinical study is usually required. The decision depends on the complexity of the drug and how well the biosimilar matches the original in structure and function. For newer, more complex biosimilars like antibody-drug conjugates, clinical trials are almost always required.

What role does automation play in biosimilar manufacturing?

Automation reduces human error, contamination risk, and variability. Robotic systems handle vial filling, sterile transfers, and packaging. Real-time sensors monitor critical parameters like pH and oxygen levels during production. AI models predict quality issues before they happen. This helps manufacturers maintain consistency across batches - which is essential for regulatory approval and patient safety.

Why are single-use bioreactors becoming popular for biosimilars?

Single-use bioreactors eliminate the need for cleaning and sterilizing stainless steel tanks, which saves time and reduces contamination risk. They allow faster changeovers between different products, making them ideal for smaller manufacturers who produce multiple biosimilars. They also lower upfront capital costs, making it easier for new companies to enter the market.

Are biosimilars cheaper to produce than original biologics?

Not necessarily - at least not at first. Developing a biosimilar costs $100 million to $200 million, compared to $1 billion for a new biologic. But once approved, production costs are lower because manufacturers don’t need to fund early research or large clinical trials. The real savings come from competition: when multiple biosimilars enter the market, prices drop significantly - sometimes by 50% to 80%.

What’s the future of biosimilar manufacturing?

The future lies in continuous manufacturing, AI-driven process optimization, and more sophisticated analytical tools. Instead of making batches, manufacturers will move toward steady-state production lines that reduce variability. AI will predict failures before they happen. Newer technologies like CRISPR-engineered cell lines may produce more consistent proteins. But the biggest challenge will remain: proving similarity reliably, consistently, and affordably - for every batch, every time.

Uzoamaka Nwankpa

January 5, 2026 AT 04:54Biosimilars are the ultimate test of human patience and precision. One tiny shift in oxygen levels and suddenly your $50 million batch is just expensive soup. No wonder so many companies fold after three tries.

Chris Cantey

January 7, 2026 AT 03:41It’s not manufacturing-it’s alchemy with a PhD. We treat living cells like they’re machines, but they’re not. They’re ecosystems. And we’re trying to replicate a symphony we never heard, only saw in a blurry photo.

Abhishek Mondal

January 7, 2026 AT 08:09Let’s be clear: glycosylation isn’t a ‘hurdle’-it’s a fundamental epistemological limitation of reductionist science. You cannot reduce a biological system’s emergent properties to a set of process parameters. The very notion that you can ‘match’ a biosimilar is a Cartesian delusion. The cell is not a reactor; it’s a phenomenological entity. And you? You’re just a data collector in a lab coat.

Oluwapelumi Yakubu

January 8, 2026 AT 15:36Man, this whole thing is wild. Think about it-we got cells doing ballet in a vat, adding sugar decorations like they’re decorating a cake, and we’re out here trying to copy the dance moves blindfolded. And the kicker? If one sugar’s out of place, your body might throw a fit. It’s like trying to replicate your grandma’s stew without knowing if she used cinnamon or just really loved her spoon.

Terri Gladden

January 9, 2026 AT 11:20I just read this and cried. I mean, imagine spending 10 years on this, losing millions, and then a fridge breaks and BAM-your life’s work turns into trash. I’m not even in pharma and I feel emotionally drained. Someone needs to make a documentary about this. Like, NOW.

Akshaya Gandra _ Student - EastCaryMS

January 10, 2026 AT 06:48Wait so if the cell line changes its glycosylation because of stir speed… does that mean the drug is kinda alive? Like… is it a living thing? I’m confused. Also typo: ‘bioreactor’ lol

en Max

January 11, 2026 AT 07:40It is imperative to recognize that the regulatory paradigm for biosimilars is predicated upon a holistic comparability assessment, encompassing structural, functional, and immunological attributes. The process-driven nature of these products necessitates continuous quality by design (QbD) frameworks, wherein real-time process analytical technology (PAT) serves as a critical control strategy. Failure to implement such systems constitutes a non-trivial risk to patient safety.

Angie Rehe

January 12, 2026 AT 20:55So you’re telling me a $200M drug can be ruined because someone didn’t stir the tank right? That’s not science-that’s a horror movie. And the FDA lets this fly? This is why healthcare costs are insane. Someone’s getting rich while patients suffer. Fix this. Now.

Jacob Milano

January 14, 2026 AT 10:11Man, this is the most beautiful mess I’ve ever read. It’s like watching a master chef try to recreate a dish they tasted once, 20 years ago, in a foreign country-except the recipe’s written in a language that doesn’t exist anymore. And the ingredients? Alive. And moody. And they hate Mondays. But somehow, they make it work. Hats off.

Aaron Mercado

January 14, 2026 AT 22:05Who cares if it’s hard? People are dying waiting for cheap insulin. This isn’t ‘science drama’-it’s criminal negligence. If you can’t make it right, don’t make it at all. Stop playing with living cells like they’re Legos. Lives aren’t experiments.

Dee Humprey

January 15, 2026 AT 03:53Just wanted to say: the fact that anyone gets this right at all is a miracle. 🙏 Seriously. Behind every biosimilar vial is a team working 80-hour weeks, sweating over data, fixing one tiny variable at a time. We need to celebrate these people. Not just the big pharma names-the lab techs, the process engineers, the QA folks who catch the error before it leaves the plant. You’re the real heroes.

John Wilmerding

January 16, 2026 AT 10:45While the technical challenges are indeed formidable, the broader implication lies in the democratization of access. The emergence of single-use bioreactors and continuous manufacturing platforms represents a paradigm shift in scalability and cost-efficiency. These innovations, when coupled with AI-driven predictive analytics, may ultimately reduce the entry barrier for emerging-market manufacturers-thereby accelerating global access to life-saving therapeutics.

Vikram Sujay

January 17, 2026 AT 15:00This is not merely a manufacturing challenge-it is a meditation on the limits of human control over nature. We seek to replicate the sacred complexity of life, yet we are bound by our tools, our measurements, our arrogance. The biosimilar is not a copy. It is a homage. A quiet, costly, brilliant act of humility in the face of biology’s mystery.